Humans like to celebrate anniversaries during their lifetimes in fives and tens, which I like to think is a direct reflection of a much longer evolutionary heritage. For instance, why fives and tens, and not, say, threes or sevens? Look at your hands and feet, count your fingers and toes, and see what totals you get for each appendage (yakuza excluded). These numbers are a result of our having descended from synapsids (“mammal-like reptiles”) that likewise had five digits on each end of four limbs. In fact, all mammals are synapsids, and the last common ancestor synapsids shared with dinosaurs and other egg-laying reptiles was more than 300 million years ago. Humans and most other mammals don’t lay eggs (albeit, some placental mammals like to hatch from eggs), but a few still do – monotremes, such as platypuses and echindnas – thus demonstrating a lingering trait of this reptilian ancestry.

So it was this week that I was reminded of a five-year anniversary, the evolutionary history of mammals, and our long-lost connection to dinosaurs, thoughts that all coincided as they were triggered by remembering the Dinosaur Dreaming dig site in Victoria, Australia.

No, these people are not incarcerated and carrying out their sentences by cracking rocks all day in the summer sun. They actually are: volunteers at the annual Dinosaur Dreaming dig site in coastal Victoria, Australia; looking for fossils of Cretaceous dinosaurs, mammals, turtles, and other animals; and very much enjoy doing this. Really.

In early February of 2006 (yes, five years ago), I traveled to Melbourne, Australia for a four-month sabbatical from my teaching position at Emory University, the first (and perhaps last) I had been granted. Before leaving, my stated goal was to work on a science-education project with Patricia (“Pat”) Vickers-Rich, a paleontologist and professor at Monash University, as well as the director of the Monash Science Education Centre. (Let’s just say Pat wears a lot of hats, all of which look quite stylish and are completely appropriate for each given occasion.)

Within the first week of my residency at Monash, Pat’s husband – paleontologist Tom Rich of the Museum of Victoria (mentioned in earlier entries of The Great Cretaceous Walk) – invited me to visit the Dinosaur Dreaming site with him for the final weekend of the 2006 dig season. The site, which is only about a two-hour drive from Melbourne, had been investigated and excavated for Mesozoic vertebrate fossils since 1994, but for only a month once every year, typically in February, toward the end of the Australian summer. I was thrilled to be invited to this paleontologically significant place, and I enthusiastically accepted Tom’s generous offer.

Tom Rich’s bumper sticker was only telling part of the story: he does indeed brake for dinosaurs, but he comes to a full stop, gets out of the car, and stays a few days for Cretaceous mammals.

I remember that day very clearly, and probably will for the 10th, 15th, 20th, and 25th anniversaries (No guarantees after that last one, though.) During the otherwise uneventful drive to Inverloch, Victoria, I excitedly talked with Tom about the paleontology that had been done in this area, and occasionally took in the rolling green hills and gorgeous blue skies of the Victoria countryside. Once we caught our first brief look of the tan-brown cliffs of the coast, I smiled: it was my first sighting of the Cretaceous rocks of Australia. Little did I know then how many of those rocks I would see in the next five years (especially in 2010), and how much I would scrutinize and beseech them to reveal their ichnological secrets. But that’s the problem with predicting the future: you just don’t know it until it happens, and even when it is happening, you still might not connect it to the past.

My first up-close view of the tasty Cretaceous outcrops at Flat Rocks, near Inverloch, Victoria. The people are part of the dig crew in February 2006, and they were pumping seawater out of the man-made depression going into the bone-bearing layer of rock, a daily ritual during the dig season. For those of you from the southeastern U.S., note the lack of kudzu and other vegetation covering the rocks, a distinct advantage in prospecting for trace fossils. But then you have to deal with the tides. Oh well. If it isn't one thing, it's another. It's always something.

The Dinosaur Dreaming dig site is also referred to as Flat Rocks, an informal name applied by people to this small area of the coast. Unimaginatively (or appropriately), it was given that name because of the broad, flat platform, formed by beds of Cretaceous sandstones and conglomerates that dip gently to the east and are planed off by marine erosion. Oh, did I mention this dig site is drowned by high tides twice every 24 hours? The bone-bearing bed that attracts so much attention from the volunteers happens to be in the intertidal zone on the marine platform, so dig crews can only break up the hard rock to look for bones during low tides. This odd circumstance certainly goes against the stereotype of dinosaur dig sites taking place in dusty deserts, but the crews that work here do not concern themselves with conditions elsewhere, and have dealt with their situation admirably.

If you want to get more bones from the Dinosaur Dreaming bone bed, you either have to drain it after each high tide, or hand out snorkel masks to everyone. They opt for the former, and I don’t blame them.

The bone bed extends up above the shore at Flat Rocks and is in the main cliff-face, marked by Tom Rich's foot here, but unfortunately is not as productive as the part that's underwater much of the time. Go figure. And no, I have nothing to say about Tom's fashion choices in headgear, although I personally would have gone with a teal keffiyeh, rather than basic red.

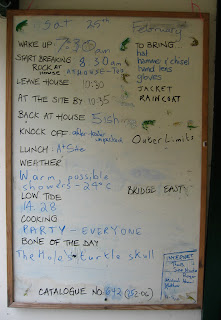

Because of these high tides, and to make maximum use of the time when volunteers are at the site, they haul back heaps of rocks to a rental house, which serves as “home” for most crew members, even if only for a week or two. What do they do then – drink slabs of beer and tell tales of what bones they found? If only. Instead, they sit down to break up the rock into sugar-cube sizes, looking for small, fractured bits of dinosaur bones or teeth, or the rare (but much celebrated) mammal jaw. Regardless of whether it belongs to a dinosaur, mammal, or other vertebrate, a “bone of the day” is often declared, though, and at the time I visited, this was announced on a bulletin board outside the house.

Why was everyone feeling the Dinosaur Dreaming blues? Is it because of the several hundred kilograms of rocks that need to be fractured into tiny bits while searching for elusive fossils?

The news you need to know each day for the Dinosaur Dreaming dig site. As you can see, the “bone of the day” on February 25, 2006 was a turtle skull. Not surprising, as the site manager was (and still is) Lesley Kool, and she loves turtles. (Incidentally, she is the inspiration for the name of Koolasuchus – the youngest known temnospondyl amphibian in the geologic record, coming from the Cretaceous of Australia.) My favorite notice on the bulletin board? The notice about the PARTY.

After a beautiful little mammal mandible was found from the Dinosaur Dreaming site in 1997, followed by more mammal jaws and teeth in ensuing years, people associated with the site began joking that the locality should be nicknamed “Mammal Dreaming.” Tom Rich, originally a paleo-mammalogist in his interests and training, thus fulfilled his long-held dream of studying Cretaceous mammals in Victoria.

Logo for the Dinosaur Dreaming t-shirt in 2007, showing a typical Australian irrelevance for what were arguably the most scientifically important fossils to come out of Flat Rocks. But, you have to admit, it’s pretty darned funny, right up there with the recent depiction of a "Thunder Thighs" sauropod (Brontomerus) punting a Utahraptor.

These finds were indeed rather important, including jaw bones and teeth of the oldest known placental mammals (Ausktribosphenos nyktos, Bishops whitmorei) and monotreme mammals (Teinolophos trusleri) in Australia, but they are exceedingly tiny (mere millimeters long), requiring much processing of rock, sharp eyesight, and the right search images. In short, this dig site requires some commuting, draining, breaking, squinting, sweating, swearing, and lots of other active verbs that only overlap in a few ways (mostly the swearing) with, say, most dinosaur dig sites in the western U.S.

Going back to February 2006, I must confess that I was awestruck at the opportunity to visit Dinosaur Dreaming and meet the people involved with it: a fanboy, you might say, one who had read Dinosaurs of Darkness from cover to cover and knew all of the names of the people associated with the Victoria dinosaur prospecting and digs over the years (including the legendary Dinosaur Cove). Indeed, I had to ask someone there to pinch me to make sure I wasn’t dreaming. (Which actually did not go over as well as I expected.)

Anyway, I had a few agenda items in mind that fine February weekend, all of them ichnological. For example, were there any fossil invertebrate burrows preserved in the sandstones and conglomerates? If so, these could be used for discerning the original sedimentary environments entombing the bones. Were there any tracks of the same animals whose bones had been washed into a stream 115 million years ago, such as those of dinosaurs, birds, or mammals, showing that they also lived in the area where parts of their dead bodies rested? How did any trace fossils I might find relate to the original environments of this place, when it was snogging with Antarctica and located at about 75° latitude south?

What happened that weekend in a paleontological- and ichnological-discovery sense has already been covered in previous entries (here, for example), and I won’t say, “and the rest was history” (because that would be a cliché, which I avoid like the plague). There are other memories showing why it was an extraordinary weekend, some comical, others magical, such as when:

• One of the long-time volunteers – Mary Walters, who I had just met – and I sped along a dark road in the Victoria countryside searching with the car’s headlights for my field boots, accidentally left on the top of Tom Rich’s Land Rover and unnoticed by him as he drove off. During our madcap excursion, we found one boot and two socks: the other boot was never found. (It was OK, though, as Gerry Kool gave me a pair of “Blunnies” (Blundstones) the next day to wear. And I still have them.)

• During my first day of scouting for trace fossils, I couldn’t help but notice a small snake, surely venomous (this was Australia, mate) that wriggled desperately on a sandy area of the beach, trapped at the base of the cliff. I had no idea how it got there, but it needed to go somewhere else. I managed to coerce it into my field hat, carried it to a vegetated drainage several tens of meters away, and released it. Intrigued by this ominous experience, I walked back to the spot where it had been flailing. Just above there was a fossil invertebrate burrow, the first I had found at the site. Thanks, snake.

• Mike Cleeland, longtime volunteer and an extraordinary fossil finder, sang at the “closing ceremony” for the 2006 dig season that certainly fit with the theme of Dinosaur Dreaming: To Dream the Impossible Dream. (I only wish he had done My Way, but somehow blending the Frank Sinatra and Sid Vicious versions). This song was preceded by the sudden appearance of a mother brush-tailed possum, carrying her babies on her back as she walked along the top of a wooden fence, as a dog barked energetically at them in the adjoining yard: placental and marsupials meeting in the present, with fossils of their relatives locked inside nearby Cretaceous rocks.

• Awards that followed Mike’s entertainment, some of which employed numerous inside jokes that no doubt multiplied exponentially during the dig. The camaraderie was palpable and warm. I could see how this event happens every year: it’s not really so much about the science, but the people.

The close of the 2006 Dinosaur Dreaming dig, celebrated with awards, stories, thanks, music, and adult beverages. From right to left: Wendy White, Lesley Kool, John Wilkins, a wayward dingo (cleverly disguised as David Pickering, even down to the beer in his paw/hand), Mary Walters, and Tom Rich. Note the photo bomb in the lower left, done by a cane toad: cheeky buggers.

Five years ago, this was a start of a new chapter that introduced me to a group of colleagues and friends in a place far away from where I sit now in Georgia, USA. So when I see pictures of Flat Rocks and the antics (and oh yes, fossils) of the 2011 Dinosaur Dreaming dig, including people I not only know but am quite fond of (in a burly, mateship sort of way), I smile and remember that time five years ago, and imagine years of science and friendship extending well into the future, bound together by the remains of Cretaceous lives.

One of the first sights of my visit to Flat Rocks in February 2006, the banner for Dinosaur Dreaming. It's still going up at the same spot every February, hopefully for as long as the bones reveal themselves. Want to volunteer for future digs? Just let them know.

In closing for this time, an emotionally moving and beautiful song (From Little Things, Big Things Grow) performed live by Australian musicians Kev Carmody, Paul Kelly, and John Butler. The song is actually about indigenous land rights in Australia, but its refrain applies to just about anything in life, including Cretaceous mammal jaws, trace fossils, and small snakes that point the way to trace fossils for visiting Yank ichnologists.

I read every word and it was very interesting. I love getting these insights into the world of paleo/ichno!

ReplyDelete